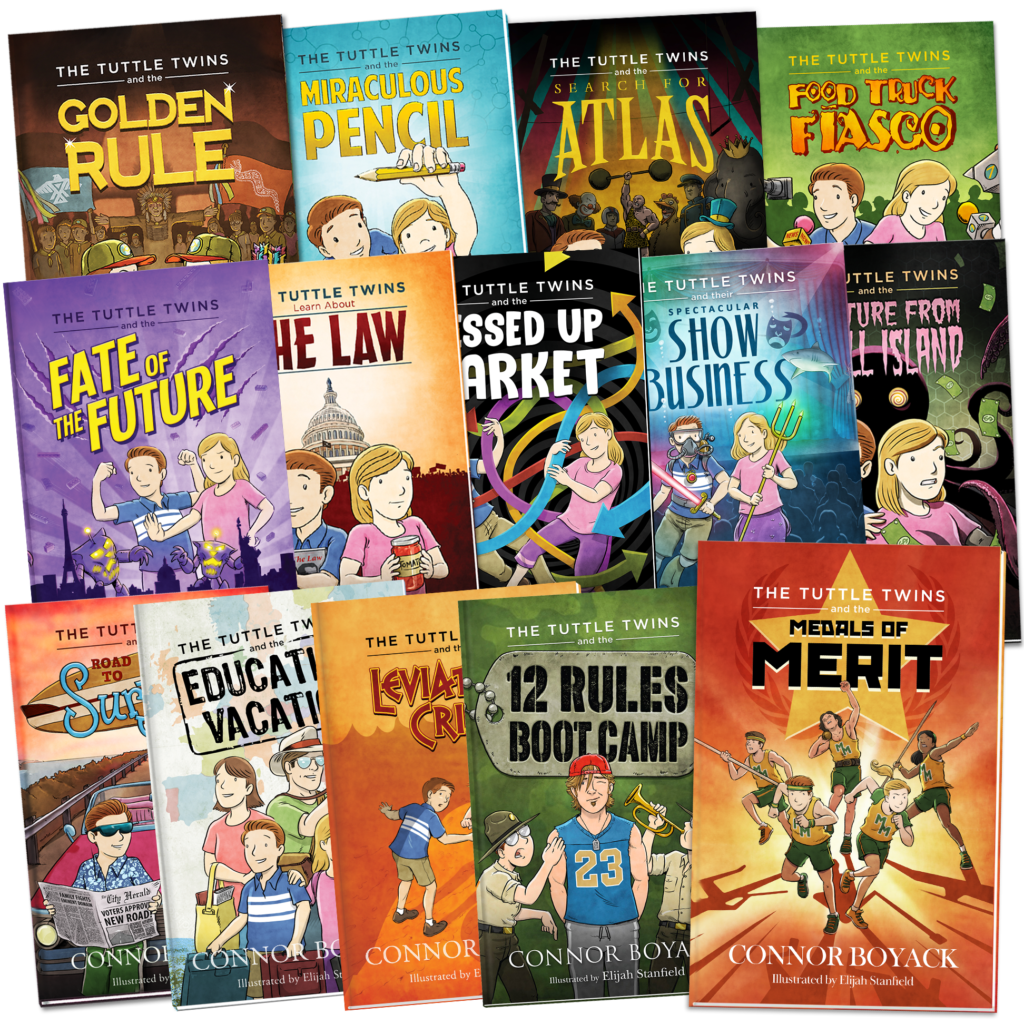

THE TUTTLE TWINS BOOKS

Teach Your Kids the Principles of Liberty

Empower your family with engaging stories that inspire freedom, entrepreneurship, and personal responsibility—without the political spin or media agenda.

Give your child the tools to think critically, dream big, and become a force for good.

Copies Sold

Worldwide

Finally, a New Kind of Education

That's Taking our Nation by Storm

“I think my kids now understand more about how the free market works than most of Congress… these books need to be read by everyone, ASAP!“

Empower Your Children

You might be wondering:

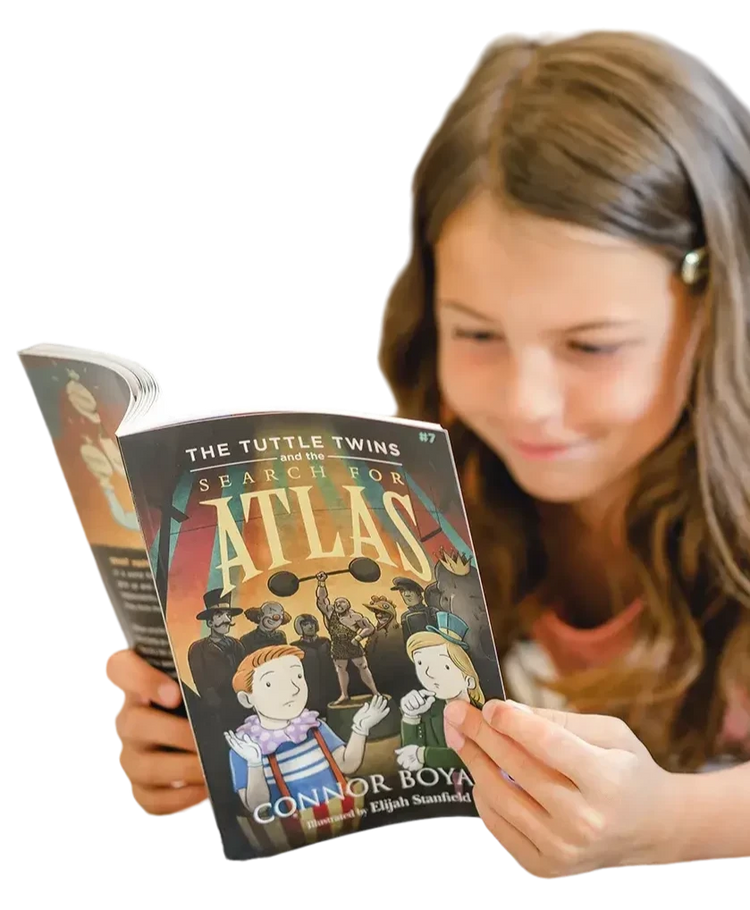

KIDS

Teach relevant freedom-based concepts that most of us were

never taught as kids. These stimulating stories encourage

children ages 5-11 to make sense

of the world.

TODDLERS

Introduce big ideas to your (very!) little ones through these children's board books. Join the Tuttle Toddlers on their learning journey as they practice the ABCs and 123s of some important topics!

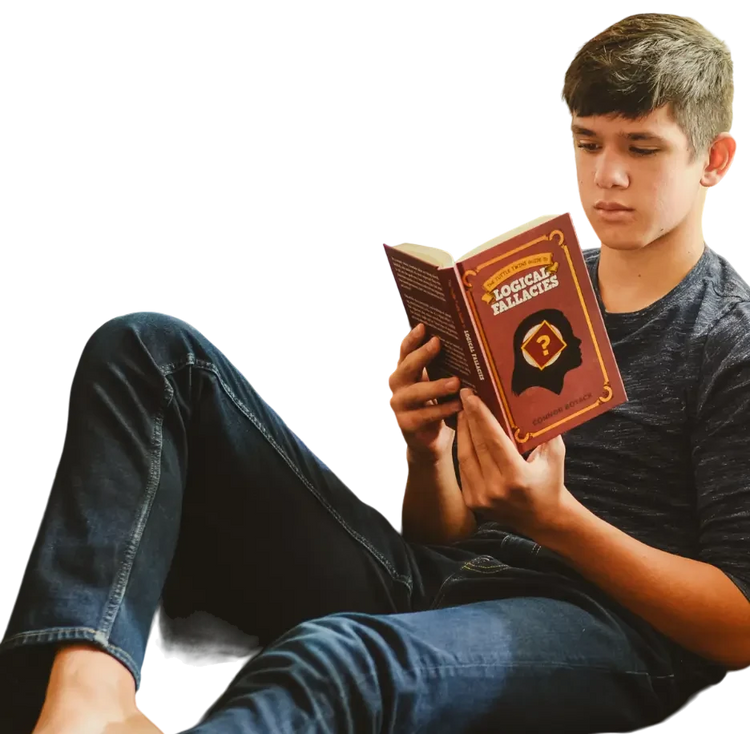

TEENS

Choose from both fiction stories (like the “Choose Your Own Adventure” books we grew up on) and nonfiction guidebooks, teaching things like entrepreneurship, critical thinking, and courage.

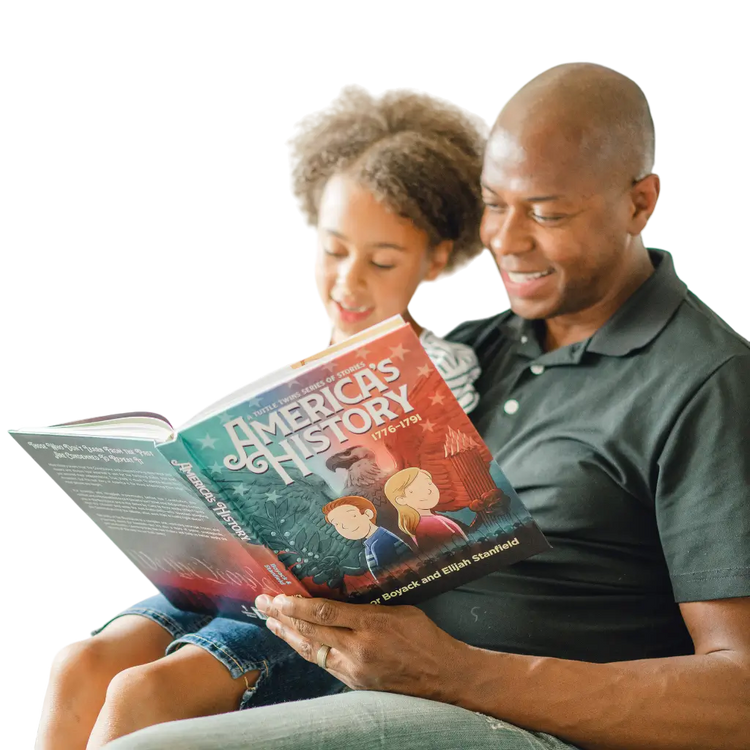

Parent with Confidence

Establish Core Truths

Bond as a Family